| |

|

|

An Irish Spring - 1984

The wild and windy March once more

Has shut his gates of sleet,

And given us back the April time,

So fickle and so sweet.

(Alice Cary, 1820-1871)

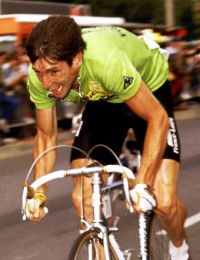

Sean "the New Cannibal" Kelly |

April is without doubt the most anticipated month on the cycling one-day race calendar. Each year it traditionally hosts three of the classic ‘Five Monuments’ (Tour of Flanders; Paris-Roubaix; Liege-Bastogne-Liege). For those living in the Northern Hemisphere the month of April is, as Alice Cary wrote, so fickle and so sweet. Some years the often the long and hard winter refuses to leave with snow and icy rain still dominating and making many believe that winter will never pass. Yet other years Mother Nature will deliver magical warm sunny days to hasten the onset of summer.

For over 100 years the April classics have enthralled cycling fans. ‘Flanders’ is famous for it’s 20 or so Belgian cobbled climbs and ‘Roubaix’ is famous for it’s notorious cobbled roads passing through the former battlefields of World War I in Northern France. ‘Liege’ has gained it’s reputation for the incredibly difficult route that takes it through the Ardennes Forest and the area famous for World War II’s “Battle of the Bulge”. When Mother Nature lays down her winter-like weather on any of these races, epic conditions prevail and epic battles ensue. However even in dry conditions it is no picnic. Particularly in the Paris-Roubaix, dried mud from the Flanders fields is kicked up by riders and support vehicles to create a chocking cloud of dust.

It was in these great races of April that Ireland’s Sean Kelly cemented the foundation stones to his great legacy. During his career he won 9 ‘Monuments’ which alone would have been enough to make him one of the greatest riders of all time. But Kelly was one of that now, all but extinct breed, who raced the entire season. His record shows one Grand Tour victory (Tour of Spain, 1988), 4 Green Jersey wins at the Tour de France and 7 victories in the Paris-Nice stage race. In all Kelly claimed 193 professional race wins, a number only bettered by the greatest of all time, Eddy Merckx.

Since announcing his arrival at the top in 1978 when he won Stage 6 at the Tour de France, he had been building his score card with numerous victories all over Europe. He hit the big time in 1980 when he claimed the Green Jersey overall at the Tour of Spain (he went on to repeat this feat at three more times). To most observers at the time Kelly had become the pre-eminent road sprinter of his era. But in 1982 he demonstrated his all-round capabilities when he won the Paris-Nice (he went on to win this race 6 more consecutive years; a record). By now Kelly was feared in any type of race, but instead of it becoming harder to win, the quality of the wins grew in number. He hit the ‘Monument’ jackpot in 1983 when he won his first (of three) Giro di Lombardia.

When the 1984 season opened with the (then) traditional races around the Mediterranean coast, Kelly hit the peloton hard with a fine win in the Grand Prix d’Aix-en-Provence. This was soon followed by the Paris-Nice which was won more by his superior control of the peloton than by exceptional exploits. Kelly’s star was rapidly rising with professional maturity. It is worth noting that the cycling world believed that the Paris-Nice now belonged to Ireland for Stephen Roche had won it in 1981 and then Sean Kelly made it his personal property until 1988!

St. Patrick’s Day 1984 was slated for the season’s first ‘Monument’, the Milan-San Remo. Kelly was, with good reason, the big favorite. In that era the great Irishman had plenty of English speaking ‘mates’ to chat with in the bunch. Greg Lemond (reigning World Road Champion), fellow Irishman Stephen Roche, Robert Millar, Scotland and the great Australian rider Phil Anderson. As it transpired, Anderson was not in a talkative mood that day as he spent 75 miles in a lone break and was not caught until the race ascended the Cipressa climb. All the big favorites hit the final climb, the famous Poggio, together. Half way up, Italy’s great former World Champion and multiple classics winner, Francesco Moser, opened a gap and only Kelly could get back up to him. They crested the climb together but were captured by the small chase group on the descent into San Remo. In the streets of the city Moser jumped again and held his gap to the line. Kelly made a serious tactical error in believing that his arch enemies, the Panasonic Team, would chase the Italian down. Had that happened the race would have been his (he actually came in second 20 seconds behind Moser).

Sean Kelly on the cobble of Paris-Roubaix

|

Just two weeks after Paris-Nice, and having just ridden the Milan-San Remo, Kelly lined up for the Criterium International. This two-day, three-stage brute is often described as a mini-TdF. In 1984 both days were blessed with miserable cold rain and apparently this reminded Kelly of his native Ireland as he revelled in the conditions. Stage 1 ended in a bunch sprint victory for Kelly. The next day saw Kelly simply ride away from the field and win from Pascal Simon by 2 minutes with riders like Roche, LeMond and Hinault even further back. The final stage (that afternoon) was a 12.5km individual time trial. Kelly had no reason to ride hard as the overall GC was all but won. But Kelly did not know how to take it easy, every race was there to be won. Not surprisingly he rode his heart out and won the time trial by 3 seconds from Stephen Roche. This crushing performance produced his second overall Criterium International win and he was to win the race one more time, in 1987.

April 1984 arrived and Sean Kelly was the undisputed ‘King’ of the peloton. Even Merckx had not opened a season with such a string of brilliant performances. Now many were giving Kelly the ultimate accolade and had dubbed him the “new cannibal” (Merckx’s nickname had been ‘the cannibal’). All this adulation and recognition was all well and good but Kelly was a seriously marked man as the peloton lined up for the second ‘Monument’ of the season, The Tour of Flanders. The tension amongst the top riders showed it’s ugly head when Roger De Vlaeminck ‘Mr. Paris-Roubaix’, almost started a fist fight with Kelly as they struggled up the fearsome cobbled Koppenberg climb. The cut and thrust attacks and counter attacks whittled the race down to a small group of leaders. Every man left was watching Kelly and it was opportunist Johann Lammerts of the Panasonic team who took flight with 4kms remaining. Meanwhile everyone else just sat and waited for the great Irishman to close the gap down. That did not happen and Kelly, as mad as hell, plastered them all in the sprint for second place.

Mid-April 1984 and it was time for what many believe is the greatest ‘Monument’ of all, the Paris-Roubaix. Kelly was yet again lining up but now ‘expert observers’ were saying that he still lacked in self confidence. In their opinion he should have won both the Milan-San Remo and Tour of Flanders. Even so his form was so startling that very few riders could even hang on to Kelly’s back wheel once he decided to put it into overdrive.

So basically the strategy was simple, avoid the carnage of endless crashes on the gnarly cobbled roads and then avoid making tactical errors that let a rider slip away at the end of the race.

Kelly and Roger De Vlaeminck on the Koppenberg |

While ‘Flanders’ had been run off under dry conditions, ‘Roubaix’ greeted the riders with raw, wet conditions with slimy mud awaiting them on the cobbled sections. Two riders had escaped the main field with about 65 miles to go. They were left there to suffer by the ever dwindling bunch until Kelly himself leapt from the chasers with about 25 miles to go. He was quickly chased down by Hennie Kuiper (who himself tasted victory in this great race). But Kuiper could not hang on to the Irish express and dropped back. Astoundingly, Rudy Rogiers achieved what very few could claim as he then went after Kelly and closed down a 30 second gap. Once the junction was made Kelly did most of the work to catch, and then drop, the two leaders. This time Kelly was in complete command as they entered the Roubaix Velodrome. He calmly reached down and tightened his toe straps. After the first lap he jumped Rogiers on the back straight and cruised home with a 10 bike length lead.

It was now the end of April 1984 and “public enemy #1”, Kelly, had lost none of his fire as he set out on the road from Liege to Bastogne and then back to Liege. The legendary climbs of this fabled ‘Monument’ were waiting for the race under mild, dry weather. By contrast the competition was in a stormy competitive mode with the cream of the European professional peloton not about to let Kelly ruin their day again. The fans were treated to “one of best races for years”. Greg LeMond, Bernard Hinault, Laurent Fignon and Joop Zoetemelk (all TdF winners during their respective careers) battled viciously as did other notables like Phil Anderson, Robert Millar and Claude Criquielion. In the end nobody could open a decisive gap. Meanwhile Kelly rode a very intelligent race marking every move. On the interminable drag up through the city of Liege only seven riders were left in the leading group, and Kelly was one of them. Nobody else stood a chance in the final sprint! Perhaps as astounding as Kelly’s win was the fact that the podium comprised three English speaking riders; Kelly, Anderson, LeMond. Nobody could remember that ever happening before at the elite level of professional cycle racing.

Kelly finally retired from racing in 1994. After firmly establishing his position at the top of professional cycling in the spring of 1984 he went on to claim two more Green Points Jersey’s at the TdF, five more ‘Monument’ victories, a Grand Tour (Tour of Spain, 1988) and four more Paris-Nice wins along with endless other wins.

But to race fans everywhere, Kelly always evokes memories of an incredible Irish Spring - 1984

Return to Velo Vignettes >>> |

|