An Enduring Legacy

When you study the history of the birth of nations you learn of the incredible struggles, intrigues, wars and hardships endured before a nation finally settles into its peaceful identity. While cycling has not suffered wars in the usual sense, it certainly has seen its fair share of intrigues, cheating, brutality and a macabre fascination for pushing the athletes to the brink of human endurance. With the exception of the Vuelta a España, cycling's premier events all started during the ‘Golden Age' of cycling (1890 until the beginning of the Great War in 1914). One has to consider that at that time roads were not as we know them today. Most were little more than cart tracks, except maybe in the larger towns that had cobbled streets and some even had the first asphalt roads. So imagine racing a very heavy steel bicycle over such terrain and over distances often close to 300 km in one day.

| Part 3: Mortals and Immortals |

Building the Legend

Today it is hard to imagine the astounding impact that those early fast moving cyclists had on citizens who rarely traveled faster than by foot or horse carriage. To see these ‘cyclists' on strange machines appear from places that they could only imagine and then disappear out of town into other unknown territory was simply awe inspiring. For much of this period the racing cyclist was the fastest moving vehicle on the road.

The concept of distance fascinated the general public. During the ‘ Golden Age ' the average citizen rarely traveled more than 25 miles (40km) distant from home their entire life. That a human being could propel themselves so far, so fast, was almost beyond comprehension. Race organizers, newspapers and equipment manufacturers quickly tuned in to the opportunity presented by the bicycle. For gifted athletes bicycle races also proved a way to make good money but often at the cost of incredible endurance efforts.

With competing newspapers organizing and promoting many of the races they would create incredible public passion for their events through extremely colorful and highly detailed articles. Remember that at this time there was no radio, telephone, television or any other media as we know it today. Thanks in large part to skillful newspaper journalists, the public was extremely anxious to see these ‘immortals' come race day.

Cheating

The riders themselves were also prone to cheating; often in very creative ways. It was not uncommon for riders to disappear from a race and find a quicker way, often by train, to by-pass a large section of the race. Such skullduggery was feasible, because due to the distance of many races they often started very early in the morning while it was still dark.

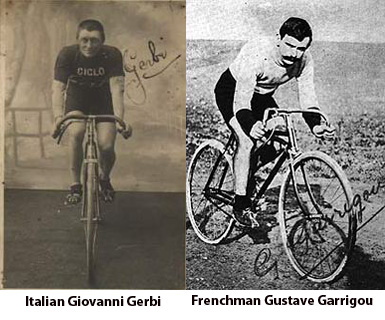

Unfortunately, public passions got out of control very quickly and unruly fans would attack riders that they did not support. Take for example the 1905 Giro di Lombardia which was won by the Italian Giovanni Gerbi. At one point in the race Gerbi was being challenged by two Frenchmen. The tifosi reacted by throwing a bicycle in front of the Frenchmen, knocking them down. As the riders were getting themselves back up a railroad crossing, a little further up the road, had closed. Gerbi had gone through and by the time the Frenchmen got there the tifosi had again gone to work by sprinkling tacks all over the road. Gerbi gained 45 minutes on the luckless Frenchmen. A gallant effort by Gustave Garrigou closed to within four minutes on Gerbi approaching the finish. Once more the tifosi took control as they arrived by car and sprinkled more tacks on the road. Yet more tifosi appeared on bicycles and paced the triumphant Gerbi to the finish line.

A year previous, the 1904 Tour de France, the problems were even more dramatic. Brutal fans had set upon many of the riders either during the early hours of the morning when it was dark or on remote country roads, beating them with clubs, spreading tacks all over the road and generally causing serious disruption to the benefit of their favorites. The riders were no saints themselves. The high stakes of prestige and money had become such an attraction that many of the riders would go to any lengths to win. At that time it was common for race results to take up to two weeks after the event before the official results were published. Such were the problems in the 1904 Tour that the organizers took from July until December to come out with their final results. The first four riders were all suspended and of these the runner-up, Pothier, was banned for life. The scandals that year were of such a magnitude that the 1904 Tour was almost the last.

Continuing Fascination

But instead of the scandals, cheating and brutality negatively affecting bicycle racing. It seemed to do the opposite. Henri Desgrange was constantly amazed that tens of thousands of people would turn out, even while it was still dark, to watch the race go by. Today, the great races that started so long ago continue to fascinate and draw fans in huge numbers to the roadsides of Europe . Many millions more also watch every single kilometer of the races on television or the Internet.

Mobile cameras bringing cycling's great races to the world through TV and the Internet (Photo Graham Jones)

Sadly, the cheating continues into a modern era (the beatings have mercifully slipped into history). We see that the 1998 Festina affair and the current Operacion Puerto affair seem to do little to stifle the enthusiasm of the fans. While the media spreads doom and gloom endlessly, the races continue to excite and draw legions of viewers.

So what is it that his continued to fascinate cycling fans for over a century? The actual courses of the major races are remarkably similar to those of a century ago. The Pyrenees, the Alps , the cobbled roads of Paris-Roubaix and the cobbled climbs of the Tour of Flanders are examples that immediately spring to mind. These race courses have etched there way into cycling folk lore. Unlike the majority of arena type sports, road cycling courses traverse a continually changing terrain and are at the mercy of the elements. Consequently a race like the Tour of Flanders one year can be a very different race the next year due to the weather conditions even though the riders pass over the same roads. The Grand Tours not only have the weather but they also have the luxury of changing their routes every year to seek out new and interesting challenges for the riders and spectators.

Quote: "To the question of which great international classic he would like to win if he had the choice, a racer will always answer, Paris-Roubaix. It is simply the most prestigious race on the calendar and even a great career will be incomplet without a victory at Roubaix". [Eddy Merckx]

Immortal Giants

Rising above the terrain, distance and weather are the riders themselves. From the very beginning they have been seen as ‘giants of the road ' riding incredible distances, incredibly fast and through every type of weather and over every type of terrain. As you step through the history of cycling you come across names that evoke legends and deep respect. It is no exaggeration to say that many great champions have been elevated to the stature of immortals. Probably the two best climbers that road cycling has ever produced were Federico Bahamontes of Spain and Charly Gaul of Luxembourg. Their exploits in the rarified atmosphere of Europe 's most demanding climbs are told and retold every year. To add to the luster of such champions cycling fans often anointed their ‘immortals' with grandiose and colorful nicknames. Bahamontes was known as the ‘Eagle of Toledo' and Gaul as ‘The Angel of the Mountains'. In Italy , the fans are particularly passionate about their cycling, and their heroes are also known by flamboyant nicknames. Fausto Coppi , Italy 's greatest cyclist of all was called “il Campionissimo” (the champion of champions).

In Belgium , the greatest accolade a rider can receive is to be called the Lion of Flanders. Former ‘Lions ' include immortals like Briek Schotte, Rik Van Steenbergen and Rik Van Looy. Today that elite title is held by Quick Steps' Tom Boonen. The greatest Belgian of all, and in fact the greatest cyclist of all time, Eddy Merckx was best known as the ‘ Cannibal ' for his voracious appetite in devouring his competition and winning races.

In CyclingRevealed's archives you will find many stories of these immortal riders; Garin, Sceur, Girardengo, Bartali, Coppi, Anquetil, Van Steenbergen, Van Looy and many others. But for every ‘immortal' there is a whole host of mortals, who suffer daily to support their team leaders, or simply to make it to the end of the race. Knowledgeable fans respect these riders as much as the great champions.

Modern Day Ugliness

Last year Operacion Puerto was revealed just before the Tour de France. On the eve of the race Ivan Basso and Jan Ullrich, who were linked to the affair, were removed from the start list. This dramatic development, that also eliminated many other riders, almost caused the Tour to be cancelled. Happily the race started and the entire three weeks were considered to be some of the best racing that the Tour has seen in its history. Perhaps more importantly the roadside crowds turned out in record numbers. The scandalous revelations did little to temper their enthusiasm.

After the Tour, the fallout from Operacion Puerto continued to wreak havoc with the fabric of the sport. Compounding this ugly story is an ongoing bitter battle that has also developed between the Grand Tour organizers (who also own most of the five monuments along with other prestigious races) and the UCI. 2007 dawned with the possibility that the entire season would be wrecked by institutional battles and power plays. The recent Paris-Nice almost fell victim to the situation. Cool heads prevailed and the race survived. In response the riders put on a spectacular show. In fact this year it seems that the quality of professional racing everywhere has dramatically improved. Perhaps this is the rider's way to combat the futility of the struggles going on behind the scenes.

A Successful Formula

The UCI is always preaching that cycling needs to change to survive. The great races along with countless others across the world have been in existence for a century or more. They have survived largely because they have adapted to a changing world by staying true to their roots. The formula established by each race has evolved into a unique character that is beloved by each succeeding generation of fans. As I write this the Tour of Flanders is just one week away. It always crosses most of the same cobbled ‘bergs' each year. Race day is an unofficial national holiday in Belgium and the famous bergs are literally shrines to the throngs of fans lining the course. If a Belgian wins (which is most often the case) then that rider is guaranteed to become a cycling immortal.

Yes, cycling does need change. Not the races, but the way the sport as a whole is managed. On Cycling.tv we are often told during ‘live' broadcasts that viewers from 120 countries are tuned in. This is the clue for change. The sport needs to market itself to a global market, to attract global sponsors and bring new international cycling champions from way beyond Europe .

Race organizers and the countries hosting them need to cater for fans traveling from all over the world to see the great races live. It is astounding how many people you meet from the entire world who make a special pilgrimage to the Alps, the Pyrenees, Paris and elsewhere on the race route. Visitors to the ‘Five Monuments of Cycling' will also be aware of roadside spectators who have traveled from distant countries to see the fabled stretches of road and the riders ‘in the flesh'. If nothing else, these international visitors bring a significant influx of foreign currency to France , Belgium , Italy , Spain , etc. For the UK , the start of the 2007 Tour de France in London is viewed as a major economic event.

If the UCI wants change, then simply continue on the crusade against drugs to develop effective controls that purge the sport of the scourge. They should also partner (not fight) with the major race organizers to maximize the value of professional cycling. At this level cycling is a business not a hobby.

As I was writing this (31 March 2007) the 50th E3 Prijs Vlaanderen from Belgium was playing live in the USA on internet TV. We were treated to yet another great race of this young 2007 season. In the Flemish town of Harelbeke thousands of fans were crammed into the streets. Their hero Tom Boonen was in the lead break of four riders. The atmosphere was electric as the passionate Belgian fans screamed their delight when ‘Tommeke' (Tom Boonen) beat Fabian Cancellara to the line. It was his fourth straight win in this race. Every Belgian in Harelbeke and across the country knew that this latest ‘immortal' Lion of Flanders had not only matched, but bettered, the four wins in this race by another Belgian immortal, Rik Van Looy. Van Looy's wins were not consecutive. While Boonen made his way to the winner's podium fragments of the peloton containing the beaten faces of racing mortals rolled across the finish line.

As the victor received his laurels, the town's church bells were loudly announcing this latest triumph and it seemed that Operacion Puerto and the UCI's squabbles had melted with the spring snow. It was almost as if the majestic church bells were signifying that these great races and the riders that contest them are truly an Enduring Legacy.

ProTour Calendar 2007

Make www.cyclingrevealed.com your homepage now.

|